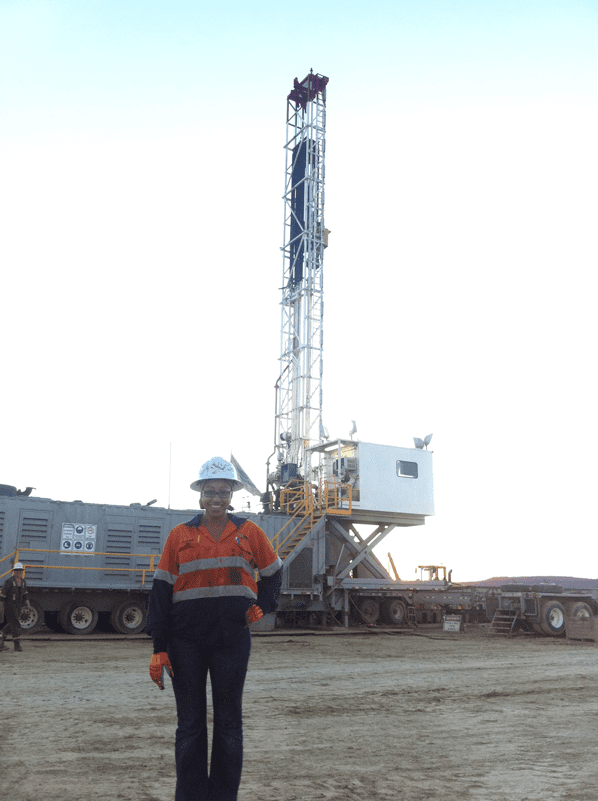

Released as part of the 40th edition of The Griffith Review in April 2013, this was my first formally published piece of work. I wrote it at [the] urging of the incredible Julianne Shultz, editor of the Review at the time, whom I served with on the Queensland Design Council. She saw in my 21-year-old self a storyteller, the potential of a writer, possibilities of a future inconceivable to me at the time. This essay came together in the mornings after 12-plus hour nights shifts, lying cross-legged on the rough pale blue sheets of my single bed in an ice cold donga, somewhere in outback Australia. “Show, don’t tell,” Julianne said to me at the time and, through draft after draft, I worked to try [to] show the world what it was to be a young, Sudanese engineer on rigs around Australia. Who knew it would be the beginning of an entirely new career?

“You’re working on the rigs?” one of the drillers from my camp asked, his voice heavy with surprise. “We assumed you were just with the camp. Respect, hey, that’s awesome, we love having chicks actually on the rigs.”

Another chimed in. “Yeah, that’s great. What do you do?”

“I’m a service hand, a “measurement while drilling” specialist. You really think we’re really welcome here?” I asked.

“Yeah! We need more of it.”

Later that day, I had another conversation that challenged this view. Clearly women in the oil and gas industry are not universally welcomed. My rig manager was quite clear about his views: “I said nope, no, absolutely not. There was no way I was going to let a female be on my crew. Everyone agreed. Sean (the manager on the other shift) even said to me that if she was hired, he would quit.”

The rig manager shrugged as he explained the reaction to a “lady” applying to be a leasehand on the rig – the lowest level job, responsible for cleaning and errands.

“I just didn’t want to deal with the extra hassle that it would bring,” he said.

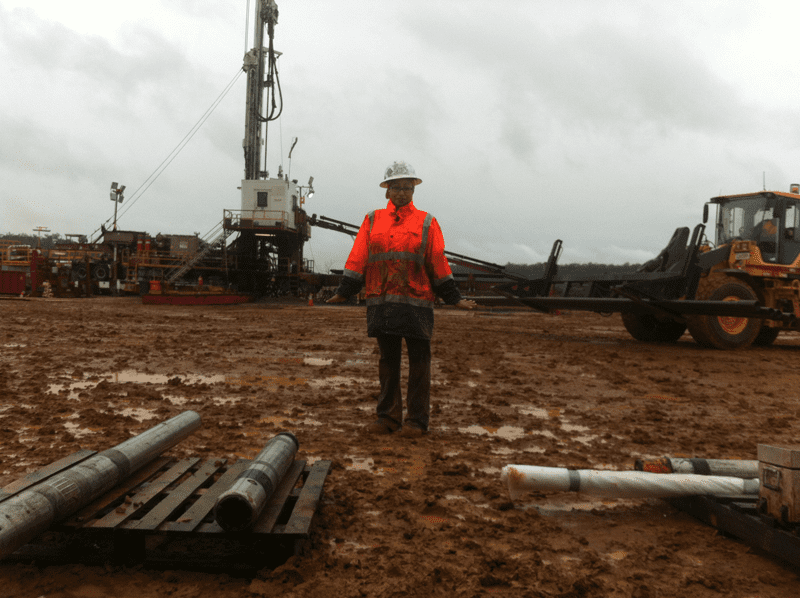

I am the only woman on the 25-person rig in Central Western Queensland.

Later that evening as I begin my regular 12-hour night shift, I touch my iPod screen and select my current favorite anthem. In a flash Seal’s velvet voice reverberates through the white earbuds. “This is a man’s, man’s world…”

Accepting that your 21-year-old Muslim daughter is going to work on remote oil and gas rigs is not easy. I am fortunate to have parents who understand (although perhaps not always share) my interest in adventure and not being ordinary. Their view is simple: As long as the rules of Islam are followed and there is a coherent and beneficial reason for me doing the things I choose, they will support me.

My parents say they weren’t sure what to expect when they immigrated to Australia almost 20 years ago, fleeing the oppressive political regime of Omar al-Bashir in Sudan. They may not have had a concrete idea of where it would lead, but I certainly inherited from them a willingness to seize opportunity and embark on adventures. That may explain how they found themselves with a daughter who boxes, designs racing cars and, while visiting family in Sudan [in 2012], got wrapped up in an attempt to overthrow the same oppressive government that forced them to leave.

They came to Australia looking for a new beginning; now they are parents of a female, Muslim rig hand.

As part of my faith, I wear the hijab (headscarf), and have been doing so since I was 10, as a personal choice. It is truly something that has become a part of my identity, and I like to be flamboyant and creative with colors and styles. My head covering on the rig is a little less obvious and obtrusive, the turban and bandana combination convenient to combine with the hardhat, and a little cooler. In true Australian fashion, however, religion is one topic that is fastidiously avoided on the rig, and people don’t always realize the significance of my head covering. It makes for some interesting conversations.

“So, when’s that tea cosy come off?”

I turned around to my colleague and chuckled to myself.

“Nah, it doesn’t come off, I was born with it, eh!”

His jaw dropped slightly, and he looked at me in confusion. “Wha-a-?”

I laughed out loud. “Nah, mate! It’s a religious thing. We call it a hijab, I guess this is the abbreviated hard-hat friendly version…”

“Oh, yeah, righto…”

He nodded, uncertain, then shrugged and went back to his meal.

When I told my family at home, my father couldn’t get enough of it.

“Let’s call you Tea Cosy now!”

***

I find I am constantly asking myself the question: Does one adopt and accept the mannerisms of the rig to “fit in,” and become “one of the boys,” not causing waves by accepting the status quo? Or should I, and other women, stick to our guns and demand change, that the men working in these isolated and testing environments change their culture and mannerisms in order to incorporate women?

It is not easy to answer. My mother sat me down before I left for my first “hitch” and gave me some advice. “Don’t forget, Yassmina, that you are not a boy, and you will never be “one of the boys.” At the end of the day, you are and will always be a woman, and a Muslim woman at that, so you must act like one and guard yourself.”

At the time, the advice jarred. I had always been “one of the boys.” It was difficult to understand why this had to change now.

The more I work in the field, though, the more I realize that things are different. Being “one of the boys” may have been appropriate at university. In the field, no matter what I do, my gender will never be forgotten. This was one of the reasons the rig manager refused to have women on his crews. “The guy that was pushing for this woman to be hired had hired his twin sister way back in the day on the rigs, so [he] had a soft spot for women on crews. He ended up having to fire her, though, because she hooked up with another crewmember. What does that tell you?”

We are faced not only with entrenched attitudes within the industry of what women are capable of, but also individual prejudices. In an industry where it seems every second man is going through or recovering from a divorce (partly due to the lifestyle), the cocktail of emotion and misunderstanding can be toxic. If I had a dollar for the number of times a coworker has said, part mirth and part seriousness – “All you damn women are the same” – I could probably retire.

Even as I write this, I feel I should apologize and add a disclaimer: Not all the oil and gas fields are like this.

Or is this just me, explaining away behavior that is common on rigs so I don’t “rock the boat” or disturb the peace and become an unwanted entity? I haven’t been able to answer these questions yet. Working on the rigs has, however, allowed and forced me to reinterpret my understanding of what it means to be a strong woman.

I was always one for doing things differently, partly because I could, and partly because I just did what I wanted. Being the first girl at a Christian ecumenical school, and the largest in Queensland, to wear the hijab when I started there in 2002 was pretty exciting. Being the first woman in my company’s department in Australia was even better. I broke the bench press record for girls at school, topped the two male-dominated classes of graphics and technology studies (woodwork), and prided myself on being able to “hold my own among the men,” physically and in banter. Although I was proud to be a woman, I had always been even more proud of my “masculine” qualities. Perhaps this is what frustrated my mother the most.

In the rigging world though, there is no mistaking the fact that I am a woman. I am not as strong as all the guys, though I can hold my own. I am not as foul-mouthed, but I can come back with a quip to keep them quiet (or laughing, depending on the situation).

“Gosh, you’ve got it pretty good, don’t you? You get your clothes washed, your bed made, your food cooked for you and, on top of that, your choice of 25 men! With no competition!” John, the campie, chortled as he opened the crib room door. “What more could a woman want, eh?”

His lined, weather-beaten face flashed a grin, showing off his multiple silver fillings as he left the shack. I shook my head slowly and laughed. What more indeed…

This job has made me realize that it is actually okay to be a woman, and being “strong” doesn’t necessarily mean being “masculine.” It’s ironic that it has taken a world renowned for its toughness to make me appreciate my femininity.

There is no doubt that it is a man’s world, but it is changing. Australia is lagging behind other countries; in Norway and Europe, women are much more routinely employed on rigs. How women change the field or change ourselves to fit in remains an unanswered question, but it will be exciting.

On another rig, I need to find the amenities. “Are the loos working?” I ask the leasehand in charge of keeping the rig clean.

“Nah, they’re probably filthy. I haven’t been in there in ages, I just piss in the paddock!”

I laughed as I walked towards the amenities shack.

“Hover!” he yells faintly.

Hover I did. As I push down the pedal of the portaloo and the stench wafts up, I shake my head and wonder: Why did I choose this job?

But I do remember. I chose this job because I love a challenge, I love working in the field, and I thrive on being forced out of my comfort zone and into environments where I have to prove myself. If I manage to smash a few stereotypes along the way, so much the better.

Excerpted with permission from the author. Talking About A Revolution by Yassmin Abdel-Magied from the chapter, “On the Rigs.” (Random House Australia; October 2022). This excerpt has been lightly edited and condensed.

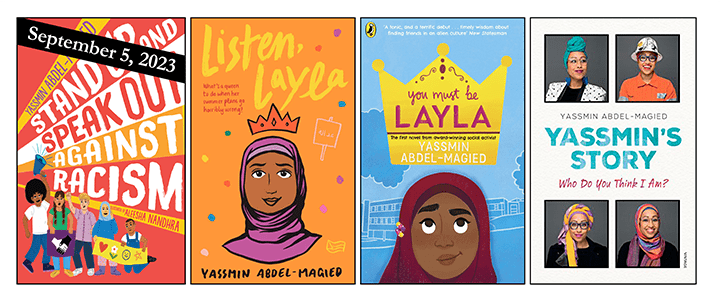

Yassmin Abdel-Magied is a Sudanese-born writer, broadcaster and former drilling engineer. Since her time offshore, the mechanical engineer has published four books, written two plays and is currently developing a number of projects for screen. An award-winning speaker and globally sought-after advisor on engaging diverse communities in STEM and inclusive leadership, Abdel-Magied has delivered keynotes and workshops in 25 countries in Arabic, English and a smattering of French. She founded her first organization, Youth Without Borders, at the age of 16, leading it for nine years before co-founding two other organizations focused on serving women of color. Her TED talk, “What does my headscarf mean to you?” has been viewed over 2.5 million times and recognized as one of TED’s top 10 ideas. In all her work, Abdel-Magied is an advocate for transformative justice and a fairer, safer world for all.

Oil and gas operations are commonly found in remote locations far from company headquarters. Now, it's possible to monitor pump operations, collate and analyze seismic data, and track employees around the world from almost anywhere. Whether employees are in the office or in the field, the internet and related applications enable a greater multidirectional flow of information – and control – than ever before.