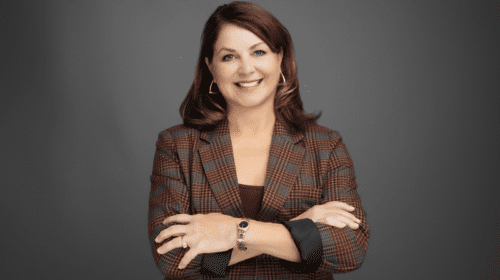

“It was the perfect time to start my business,” Tracy Lenz says of the decision to go out on her own in 2020 after nearly 15 years as a petroleum engineer. It was also the start of a worldwide pandemic.

“I had my very first client project in March, the week before everything crashed, and I had to email him the next week and say, ‘Oil and gas prices have changed a little bit. My report isn’t quite accurate anymore,’” she says, laughing ruefully.

It was a sharp contrast to the way Lenz’s career started in the mid-2000s, when “things were blowing and going.”

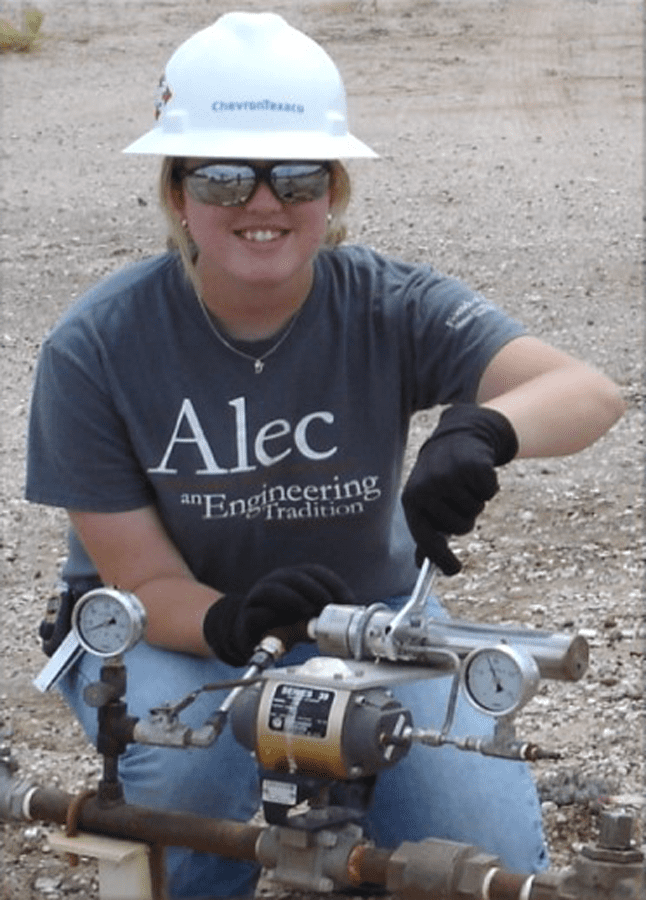

During college, she had several internships with Chevron and, after graduating from the University of Texas at Austin with a Bachelor of Science in petroleum engineering, she had her pick of jobs. She wanted to be close to the field, so she and her husband, Ryan, moved to Midland, Texas, and she worked as a field production engineer for about six months before going into the office to do workovers and waterflood management.

After two and a half years, Lenz took a transfer with Chevron to Lafayette, Louisiana, so her husband could go to graduate school. In Louisiana, she did shallow Gulf Coast reservoir engineering. “Not the big Tahiti field type projects,” but conventional wells, she says. “It was the one time in my history that I feel like all the things I learned in college applied.”

Despite the fact that she loved the culture at Chevron and knew that the large company could offer an excellent training program, Lenz wanted to work for a smaller company and eventually start her own business.

“It had gotten to the point where I was learning ‘Chevronese,’ as I called it – all the acronyms and the way they do things – and I either needed to leave or commit to it for the long haul.”

Lenz started answering recruiters’ calls and was surprised to be offered a job in Austin instead of Houston, Dallas or San Antonio. “I didn’t even know there were oil and gas jobs in Austin,” she says. “It was what I wanted to do, which was more the reserves and the economic side of the business.”

An added bonus was the fact that she and her husband have family in Austin.

Lenz accepted the position with Jones Energy. “It was like drinking from a firehose – and I loved it,” she says.

A private company at the time, Jones needed someone to handle its corporate reserves and interface with the banks, which were doing a lot of reserves-based lending. Horizontal drilling was taking off and the company was borrowing in order to drill “big dollar wells,” Lenz says.

“I would go to the bank meetings and explain the engineering. I was the translator between the engineers and the finance guys. I got to be a part of every piece of the company – from how much it took to drill a well to what percentage we owned on the land side to what taxes were being taken out – because almost everything goes into the value of a barrel that’s produced,” she notes.

The company went public a year after Lenz was hired and she was tasked with the SEC filings for the reserves. “I had to make sure everything was buttoned up and answer all the SEC questions that came through.”

At the same time, she was finishing a master’s degree in petroleum engineering, with an emphasis on smart oilfield technology, from the University of Southern California that she had originally started while with Chevron.

In 2014, the market crashed and the company, like so many others, spent the next few years trying not to go bankrupt. An opportunity presented itself for Lenz to become manager of its western assets, controlling workover budgets, working on field safety, handling mineral owner payments and managing personnel. Despite management’s efforts, the company was forced to declare bankruptcy in 2019. The new owners eventually sold to yet another company, which then decided to move operations to Oklahoma.

“There was no way I was moving to Oklahoma,” Lenz says. “I had already been planning on starting my own business for years at this point, and it was perfect timing.”

Starting a family factored into her decision as well. Lenz had a daughter in 2016. “Working 70 to 80 hours a week didn’t make sense anymore, and I was getting burned out,” she says.

Having been on the operator side for so many years, she wanted to help level the playing field between buyers, whom she felt had a distinct advantage in terms of knowledge and resources, and sellers – the land and mineral owners – whom she felt were often at a disadvantage and yet had the most at stake. Lenz opened her Christian-based boutique business, Pecan Tree Oil & Gas, to help those sellers get an equitable offer based on fair market value.

A professional engineer licensed in Texas who holds the International Institute of Mineral Appraisers certified minerals appraiser designation, Lenz follows standard appraisal and engineering practices for valuing minerals and estimating fair market value.

“Rarely do I really come across many mineral owners that say, ‘I have X net acres and it’s leased at X percent royalty,’” she says. “Most people don’t have a fully supported grasp on what they actually own.”

Mineral owners often figure out what they own based on someone offering to buy it, she says. “That’s kind of like not knowing how many square feet are in your house, but then someone offers to buy it based on how many square feet they think you have.”

When she puts it in those terms, mineral owners have a much better understanding of what is at stake, she says.

A quick summary of her advice to sellers:

- Know what you own in terms of acreage and mineral rights.

- Prices are not firm; there is always room to negotiate.

- The pandemic should not be used as an excuse not to receive a fair-market offer.

- Any unsolicited offer should be questioned.

In establishing her company, Lenz also wanted to help mineral owners at a financial disadvantage, perhaps because their properties aren’t yet paying.

“That’s where I felt there was the most inequity.”

She considered establishing a nonprofit, but didn’t want to have to wait while going through the laborious process of setting it up, so she established a charitable arm of Pecan Street Oil & Gas called Roots of Love.

“I didn’t want cost to be a reason for people not to get the information they need to make smart decisions,” says Lenz, who got her start helping mineral owners through the Mineral Rights Forum, where she is now a regular contributor.

Lenz recalled the story of a man who came to her wanting to know if he was getting a “good” offer for his minerals. Because he had told her there was only one well involved, she told him she would take a “quick look” – a concept she later expanded on to create a reasonably priced service for her clients – otherwise, it would end up costing him more than he was being paid.

After a little investigating, Lenz asked the man about the other six wells on his property, and he responded, “What wells?”

The title had gotten separated between the man’s estate, his mother’s estate and his grandfather’s estate and needed to go through the process of probate.

“He almost sold something for pennies on the dollar because of what was sitting in suspense,” Lenz says. “He was able to sell his minerals for dramatically more than what he almost sold them for before probate. Ratio-wise, it was about 30 times more.”

Looking to the future, Lenz says, “This is a growing company. I have plans for this year that hopefully will come to fruition and make it even more interesting and easier to get information and really stack knowledge on top of that. It’s a way to help make it more affordable for everybody.”

While Lenz says she doesn’t typically play the “girl card,” being a woman and a mother sets her apart in this industry. Having a child and all the things that come along with being a mother have highlighted for her the difference between the how men run things in contrast to how a mom would, in terms of the time commitment, where to work (home versus office), hours worked, as well as softer skills, such as how people talk to each other, how they treat one another, and the things they value. “It’s still a very male dominated [industry] and one of my goals is to try to lean toward at least a neutral, if not a feminine, option.”

Lenz says it’s one of the reasons she is involved with Austin Women in Oil & Gas, serving as the organization’s vice president. “It’s not so much that I’m trying to give women a secret advantage; I’m trying to help them catch up.”

This article originally appeared in the July 2022 issue of NAPE Magazine, and has been lightly edited.

Headline photo: Visiting a new well site, as asset manager for Jones Energy’s Anadarko Basin assets – and seeing snow for the first time in years – in Perryton, Texas, in 2018. Photos courtesy of Tracy Lenz.

Rebecca Ponton has been a journalist for 30+ years and is also a petroleum landman. She is the author of Breaking the GAS Ceiling: Women in the Offshore Oil and Gas Industry (Modern History Press; May 2019). She is also the publisher of Books & Recovery.

Oil and gas operations are commonly found in remote locations far from company headquarters. Now, it's possible to monitor pump operations, collate and analyze seismic data, and track employees around the world from almost anywhere. Whether employees are in the office or in the field, the internet and related applications enable a greater multidirectional flow of information – and control – than ever before.