With the recent release of the Martin Scorsese film, Killers of the Flower Moon (based on David Grann’s 2017 book of the same name), all eyes are riveted on the story of the Osage people of Oklahoma and the history behind what was known as the Reign of Terror, the horrific and heartbreaking fight over the Tribe’s oil wealth. (It has been widely reported that, at one time, the Osage were the richest people, per capita, in the world, with the Osage Nation itself saying its people were “one of the wealthiest groups.”) And, while the exploration and production of oil and gas in Osage Territory provided, and still provides, jobs for some of the Osage people, Indigenous people – American Indian or Alaska Native – make up about only two percent of workers in the petroleum fuels sector, according to the 2020 U.S. Energy and Employment Report.

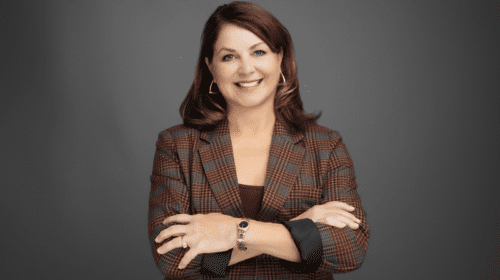

Salina Derichsweiler, the Director of Development at SunShare, is a member of the Iñupiaq group of Indigenous people (the name “Iñupiaq,” meaning “real or genuine person” – inuk “person” plus -piaq “real, genuine”).1 Her 20-plus year career in energy has encompassed the full spectrum from oil and gas to entrepreneurship and now, “I’m at a new place in life where I’m really happy with where I am and what I’m doing,” – in the renewables sector, specifically solar energy.

Describing herself as a storyteller and saying she is excited to share her story, Derichsweiler is quick to point out that Indigenous people are “not a monolith” and that she speaks for herself.

“I’m happy to share my views and what I’ve experienced and how I’ve navigated these spaces, especially as I have really entered that Tribal energy sovereignty space and renewable energy, and what it means to move from oil and gas over to renewable spaces.”

Nature Versus Nurture

In order to tell her story, Derichsweiler feels it is important to share some background information on her family of origin and the generational trauma it has experienced. Her maternal grandmother was originally from the Alaskan Native village of Kiana and was a survivor of forced assimilation and residential schools. Derichsweiler remembers her mother telling her how her grandmother’s hair had been cut and she had been forbidden to speak the Native language or practice traditional aspects of Iñupiaq culture. “It was just a really painful experience,” she says, and one that had a ripple effect for generations to come.

Despite assimilation and relocation efforts by the U.S. government again after World War II, her maternal grandfather, who was Irish by descent and had served in the Air Force, moved her grandmother and their young family to Colorado, where they lived in poverty.

“There’s a lot of domestic violence, and substance and alcohol abuse, in our family that passed down [through the generations]. My parents each had their own traumatic childhoods and that was something that was very impactful to me, [especially] as the oldest of four children. Like a lot of families, we faced significant poverty and that comes with food and energy insecurity. I really wanted out of that whole system.”

Look for the Helpers

An avid reader, Derichsweiler discovered through books and popular family TV shows of the time, such as The Brady Bunch and Bewitched, “There was this whole different world that existed” – one that she wanted to be part of.

She found a way out: education. Like many people, she remembers that one specific teacher who made a lasting impression on her and, in fact, changed the trajectory of her life. “I was seven years old and my second grade teacher, Mrs. Linda Martin, told me, “Educate yourself,” and this was a road map; it was the answer to how to change my own circumstances.”

Unlike home, Derichsweiler found school to be a place of food and warmth and attention. She loved learning and “just naturally fit in with the system,” going on to become a first generation high school graduate. However, before that, in eighth grade, students were told to lay out their plans for high school. Derichsweiler was very specific: She wanted a full ride scholarship, to graduate valedictorian, and to become an engineer. The problem was, she had no idea how to accomplish those goals on her own.

“I’m of the Mr. Rogers generation – ‘look for the helpers,’” she says, “and my helpers were my teachers, my coaches and my high school counselors.” With their advice and guidance – volunteer, get good grades, join extracurricular activities, take Honors and AP classes – and her own hard work and determination, even during a time of personal turmoil, she succeeded in achieving her goals. She had gone through foster care before middle school (which, in some ways, was reminiscent of the trauma caused by her grandmother being forced into a residential school for Indigenous people), her parents had divorced, and she had to get a part-time job out of necessity to help support her family.

A Bridge to the Future

After foster care, Derichsweiler was placed with her father, who was white, and remembers her teachers and counselors in high school convincing her that it was a good thing to state that she was the first Native American student to graduate valedictorian in her school district.

“I was still wanting to hide that part of my identity. It felt safer, I suppose, to pass as white. Now, as the world has changed, and I’ve learned about my own trauma and my own life experience, I [realize] I’ve had significant white privilege.”

“It’s only now that I’ve really sat in my own identity and said, ‘Wait a minute, is this the path where I belong?’ and that idea of bridging between two worlds and integrating two worlds has been the path I’ve taken in life.” Derichsweiler has had to reconcile and find a way to bridge growing up in poverty to becoming one of the top one percent earners; from having parents who didn’t graduate from high school to having a master’s degree; from being perceived as white to stepping into her Indigenous identity; and going from a lucrative and successful career in oil and gas to renewable energy.

“So, my whole life has become about this integration of identities and aligning with values.”

Making Dreams Come True

Derichsweiler’s career path began when she chose to study engineering, an unusual degree plan for a young Indigenous woman. “I thought [math] was the most beautiful language that explains how things work. In high school, I was doing these hands-on science classes and chemistry was another kind of language that described how things worked. I was interested in the combination of these parts and pieces, and I also wanted to make a good living. I wanted to get out of poverty and engineering is a fantastic way to do that as they’re high paying jobs.”

Even though she says she didn’t know what she wanted to be when she grew up, she had her road map, and chose chemical engineering as she felt it was a broader degree plan with greater opportunities. All of her years of hard work and studying were rewarded when she received a full scholarship to the prestigious Colorado School of Mines.

“It was an incredible way for me to be able to pay for college and do all these things I had dreamed about when I was 14.”

Fulfilling one dream, she graduated in 2002 with a Bachelor of Science in Chemical Engineering and Petroleum Refining (and later went on to earn an MBA from Pepperdine). During her time in school, she interned with Marathon Oil as a chemical engineer and then with Tom Brown, Inc., as a reservoir engineer. Like so many women, she says she “fell into” the oil and gas industry, going to work for Occidental (Oxy) as an engineer in training upon graduating.

A Change in Plans

What little familiarity she had with the industry stemmed from the fact that she had an uncle who worked for the oil and gas division of NANA, the Alaska native regional corporation that was part of the Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) with the U.S. government in 1971, something she views as a way to limit Indigenous people from enrolling and being recognized as part of the Tribe.

“I can only be a shareholder in that corporation when my grandmother or my mother dies,” Derichsweiler explains. “I can’t actively enroll when we’re all alive, so my children won’t become a shareholder until I pass, and that just seems to limit the number of shareholders in my opinion, so I think it’s a really terrible system.”

Despite that, she envisioned NANA being the place where she eventually would move her career, but she believed she needed to get training and experience with an oil and gas company first. She feels fortunate to have been hired by Oxy to work at its THUMS Island location. (The four manmade islands off the coast of Long Beach, California, were built in 1965. The acronym stands for a consortium named after the parent companies who bid for the operating contract: Texaco, Humble, Unocal, Mobil and Shell. The islands and operations were purchased by Oxy in 2000 and later spun off.) The idea, Derichsweiler explains, was “to fit within the community and be environmentally pragmatic about the extraction of oil and gas.” Said to be the only “decorated oil islands” in the U.S., they are the innovative design of landscape architect Joseph Linesch, who also created Disney’s original landscaping design.

Claiming the Right to Belong

During her time at Oxy, Derichsweiler had three “amazing mentors – all women and all in engineering or the technical realm: Ruby Kamdar-Buchanan, Janet Weimer and Jeannie Irwin,” who showed her how to navigate a male dominated industry with confidence, and helped her understand why they chose to pursue a technical role versus a leadership role, despite previously having been in leadership positions. “They really just taught me how to be that engineer and be that professional.”

Having mentors is different than having role models. Derichsweiler remembers going through leadership training at Oxy in her mid-20s (while starting her MBA at Pepperdine) and being the youngest and the only woman in that leadership training. “I remember being explicitly labeled by the trainer as an “interloper.” I said, ‘I am most certainly not an interloper; I belong here!’”

Reiterating that “we can be it if we can see it,” she made the decision that even though she didn’t have a role model, she needed to be the role model for younger female engineers and particularly Indigenous young women.

“Honestly, I think early in my career – really up until I started my own company [a few years ago] – I leaned more into the identity of being white, passing as white. I didn’t bring forward any of my own unique perspective as an Indigenous woman and part of that was because there wasn’t a role model; there wasn’t somebody who could help me see that it was safe enough to do that.”

The Freeing Power of Role Models

She would find a role model in Paula Glover, the president of the Alliance to Save Energy, whom she would meet when she the opportunity to be a Mária Telkes Fellow with the Cleantech Leaders Roundtable (CTLR), headed by then-president Jigar Shah, now the director of the DOE’s Loan Programs Office.

“As a Black woman in the energy industry, Paula Glover speaks truth to power and that is her special skill set. She was instrumental in helping me understand that my unique perspective as an Indigenous woman added value.” Glover’s influence and seeing Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, a member of the Pueblo of Laguna, become the first Native American to serve as a cabinet secretary – “she brings her Indigenous centered perspective into that role and makes decisions from that place” – were the catalysts for Derichsweiler fully embracing her identity as an Indigenous woman.

That identity was increasingly at odds on a number of levels with her role in the oil and gas industry and led her to leave the sector in 2020 and cofound a geothermal company called Transitional Energy. “Starting my own company had always been a career goal of mine. I had this dream of building a transitional company [and] it showed that you can actually plan a company that can be net carbon zero. We have a duty as energy professionals to do this for our children and for our grandchildren.”

Sharing Ancient Wisdom

Differing philosophies with her partners and the desire to spend more time with her children led to Derichsweiler leaving the company, but she ultimately found her “dream job” when she was hired for her current role as Director of Development at SunShare, where she focuses on the development of community solar in New Mexico, both within and outside of Tribal Nations and Pueblos. She says she has realized that engineering is a degree in advanced problem solving, and has provided her with a skill set that has served her well throughout her career.

“Part of my job is to be an effective translator between the western world and traditional energy development and Tribal communities. I think it is an equally Indigenous perspective to say we really need to think about how to be regenerative and sustainable, and that integrates Mother Earth, which is a closely held cultural value, but I also think it’s a closely held human value.”

As someone who grew up with energy insecurity, Derichsweiler believes access to energy is a basic human right, but emphasizes, “Our energy strategy should come with the smallest possible impact to our one home, our one planet Earth, and I just don’t think they’re mutually exclusive choices.”

1 Source: Alaska Native Language Center

Headline photo: Salina Derichsweiler shown on location in southeast Colorado, courtesy of Charlotte Derichsweiler.

Rebecca Ponton has been a journalist for 30+ years and is also a petroleum landman. She is the author of Breaking the GAS Ceiling: Women in the Offshore Oil and Gas Industry (Modern History Press; May 2019). She is also the publisher of Books & Recovery.

Oil and gas operations are commonly found in remote locations far from company headquarters. Now, it's possible to monitor pump operations, collate and analyze seismic data, and track employees around the world from almost anywhere. Whether employees are in the office or in the field, the internet and related applications enable a greater multidirectional flow of information – and control – than ever before.