It’s early morning, U.K. time, and as I’m making coffee, I find myself thinking, this will be my first interview for Oilwoman since recently leaving bp, after 15 years’ service with the company. It’s time for new horizons, and so it seems just right that for this interview I’ll be chatting with Stacey Copas, whom (unlike my other interviewees so far) I’ve never actually met or spoken with previously! I found Stacey online, after following a trail of article breadcrumbs, posts and links across the web. I was delighted that she agreed to be interviewed, and as I plug my camera into my Mac, I smile thinking of the power of technology, meaning that although Stacey is in Australia and I am in the U.K., within moments she appears on my screen and it feels almost like she is sitting opposite me. I don’t think I’ll ever stop being amazed by that!

Angela McKane: Stacey, hi! It is so nice to “meet” you!

Stacey Copas: Hello! It is lovely to meet you, too.

AM: So… you are in Sydney, correct? It is on my list to visit one day!

SC: Yes, I’m here in Sydney. I was born and brought up here; in fact, I lived here all the way through until I was 29 years of age. In the early years, starting school, I found the subjects really easy to learn – too easy, really. In year one, I would skip ahead and be completing the work for year two, but even then I was often landing in trouble for talking too much. My reports would say, “She talks too much and disrupts others,” but really it was just that I was bored.

AM (smiling): Well, hey, I always made friends with the mischief makers and talkative ones in the class at school. They were the most fun.

SC: Ha ha, yes!

AM: Did you have any big dreams or aspirations at that age?

SC: Oh, for sure. Before I even started school, I loved animals and wanted to be a vet. I’d be out there catching lizards, butterflies, spiders… you name it!

[Angela’s note: Dear reader, please be aware the spiders are the main reason I haven’t made it to Sydney yet. I gulp down some coffee and compose myself.]

AM: The spiders, yes… Did you also have a family pet that would also catch those on occasion? A nice big cat, perhaps?

SC: As it happens, yes, we did indeed have a cat! We also kept birds, and then after that we had dogs as well. I always had animals around me, which I loved. I also had sports around me. I was an athletic kid. I was the pitcher in the girls’ softball team; I was also the first girl to play soccer for the school! I was a track runner, too – every distance from the 100 meter right through to the cross country.

AM: You must have been looking ahead to secondary school, and already with a dream in mind of becoming a vet. But, then, something happened that changed everything.

SC: Yes, it was in the last couple of weeks of primary school. I’d already sat and passed the exams and got accepted into a very selective agricultural high school. It was academically really competitive, and I felt proud that I had got through on the first round! So, here we were close to the end of the year, early December, and I was round at a relative’s place. It was a super hot day, so many of the kids [and I] were round the pool in the backyard. My younger brother was there – he was 10 at the time – and some other younger kids as well.

I just did what I’d been doing every other time previously when I visited: I climbed up on the edge of the pool and dived in. It was an above ground pool, so really not deep enough but I had dived in before and this time again, and again. I kept climbing up onto the edge of the pool and diving in again. I was getting yelled at to stop that, but, you know, I was 12 and feeling bulletproof and invincible. So, I went round one more time. I had felt that with the other dives I had been splashing around too much, and I thought to myself, “How could I really perform the perfect dive?” I thought maybe if I kept my legs straighter and held my feet together, then I would glide through the water without much splashing. I took a great big deep breath, straightened my legs and held my feet together and, then, I did exactly that.

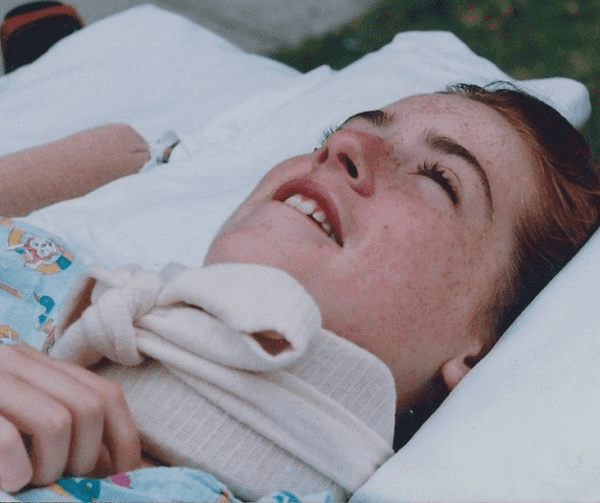

I felt the water envelope me and it felt like any of the other dives I had done before. I didn’t realize anything was wrong until I tried to engage my body to swim to the surface and found I couldn’t move at all. I was still conscious, but I couldn’t feel any pain, in fact I couldn’t feel anything. I started to panic, and was holding my breath, desperately willing my body to move so that I could attract attention but to no avail. I held my breath for as long as I could and when I simply couldn’t hold it any longer, I just had to breathe in and as a result my lungs filled with water and I lost consciousness. The kids in the pool had thought I was just mucking around at first but, when enough time passed, they raised the alarm. Someone dove in and got me out of the water, and managed to get me breathing again and then I was rushed to hospital.

In intensive care that evening, a doctor informed me that I had drowned in the pool, and broken my neck, and that I’d never walk again. I was also told that I’d be in hospital for a very long time and, sure enough, I ended up spending seven months there. It was seven months in an acute setting on a kid’s ward, and then going to a spinal unit twice a day for intense physio and occupational therapy.

AM: That must have been really grueling, both physically and emotionally.

SC: Yes, it was. The day that it happened felt like an incredibly long day, but also like it was happening to someone else; I wasn’t me. I was emotionally utterly exhausted, and hooked up to a morphine drip, of course, but I do remember two sides of me almost in conflict battling it out. One side was saying, “This is it; this is a death sentence.” And, at first, that was the stronger of the two sides. But there was another little glimmer in there saying, “No, I’ll prove you wrong.” At this point of mental anguish, the balance was tipping in favor of feeling that it was futile to even try to go on. I felt that there was no point, that I wouldn’t be able to do any of the things I used to do, and I was such a fiercely independent soul, even at that young age. I am also a really active person, so that first eight weeks, where I had to lie on my back staring at the ceiling with only these thoughts and unable to move, was a form of torture.

AM: Hmm, I can only imagine what that would be like at such a young age. Could you have friends to visit at that time? I’m just thinking, it’s tricky enough navigating girls’ friendships already at that age, especially when heading from primary to secondary school. There’s a lot to learn at that stage.

SC: It was tricky, yes. I had friends who would come in and see me, but the hospital was far and nowhere near home. It would take a couple of very long train rides to get there and it’s not like we had mobile phones to text each other back then. I was on a children’s ward, so I would get to know others on the ward but they often wouldn’t stay long. It felt more like a revolving door of different children and young people coming and going. So, it wasn’t easy, and at the same time I was also thinking that boys would never be interested in me again as well. It was a lot going on in my head; however, I did make good friendships with many of the staff on the ward. After all, I was there for months. I really had the chance to get to know them!

They also saw me progress and regain some strength and movement over that time, following the intense schedule of physio and occupational therapy five days a week every week. They also saw how hard it was. I would hold myself upright on the parallel bars but, over the course of those months, and at that age you are growing rapidly. I was getting knee pain and ankle pain. Even after I left [the] hospital, I was trying to do even more of this standing with a physio, but it got to the point where I was in pain and I realized, this just isn’t worth it. At that point, I made the decision that the wheelchair was the right answer. It would give me back my independence and get me around. I was growing so fast I had outgrown that first chair within 18 months!

AM: I am so glad you got through that time in hospital, though it must have been so tough to endure. Were you able to go on to secondary school once you were out?

SC: Well, I’d missed the first six months, and I couldn’t go to the school I’d worked so hard to get into. Apart from anything, it wasn’t accessible at all, and we weren’t mentally ready for that fight. At this point I couldn’t get around independently, and it wasn’t feasible to end up getting sent to a school that was so far away while requiring extra support. To top it off, I also started in the middle of the year and didn’t know a single soul. I pretty much just kept my head down and got on with it. Looking back, I just didn’t want to let anyone in, and like many teenagers my outlet and escape was getting drunk and stoned. Physically, I had drowned, and now emotionally I was drowning every day. I did have boyfriends through high school, but I would struggle to get close or allow myself to be vulnerable with anyone and at this stage the wheelchair had knocked my self-esteem a bit, I was convincing myself that I was no longer attractive. The teenage years are hard for all of us, and maybe especially for girls as our bodies change, and I felt that in addition I had this extra component to deal with as well. Emotionally, I went to a really dark place.

AM: Did you have any professional on hand to help with this? Like a therapist, for example?

SC: I tried, but I pretty much told them to get stuffed early on. I mean, I had some 22 year old psychology major telling me they knew how I felt, and I was like, right, sure, moving right along. I then tried to seek out therapy again but I had a really bad experience where the psychologist suggested I had an eating disorder, which I definitely didn’t! So, that created trust issues with mental health professionals for me and I felt that I was going to have to deal with this myself. I slowly began to realize that getting drunk was not the way to do that, partly as I was sinking so low I started thinking that I didn’t want to be here anymore. At my lowest ebb, the only thing stopping me was the fear of surviving, but making the situation even worse and harder to endure.

Leaving school, though, was a tremendous turning point for me. Quickly, I found that I was able to do all the things my peers were doing. I got a full time job, I got my driving license, I had a car, a boyfriend, hobbies and people who loved me. Once I was well into my 20s I had a big mental shift – an epiphany – where I became aware that I couldn’t change what had happened, but I could change the story I was telling myself about it. I realized that, well out of school, I had agency over what I would do with my life next. Gradually, that thought process evolved into deep gratitude for the learnings and perspective I had obtained as a result of what happened.

As soon as I reached that point, the opportunities just started arising everywhere! I went from floating from job to job, glad to have work but not really finding anything fulfilling, to appreciating that I could use what I had learned to make a difference for others. As a first step, I tried out getting involved in politics, joining one of our major political parties and I ended up running for local government, then I was in the Women’s Council, and the Youth Council, and then I was running for a state seat in the state elections! I did that for a few years before I started getting disillusioned with it and knew I could make a bigger difference outside the political system.

This led to me being asked to volunteer as a mentor to disabled people in the Solomon Islands. The significance of this should not be underestimated as I had never been overseas before that point and I was a real city girl. I spent a couple of weeks there, getting to know others and helping by sharing my personal story. Returning from that to a “normal” day job left me with an inner feeling that I needed to be doing something more and so, a year later, I took a leap of faith and started my business, The Academy of Resilience. I’d been receiving some personal development coaching in the lead up to making that call, and the coaches I had helped me see that there was such value in sharing my experience, [so] why stop with occasional volunteering, why not really go for it?

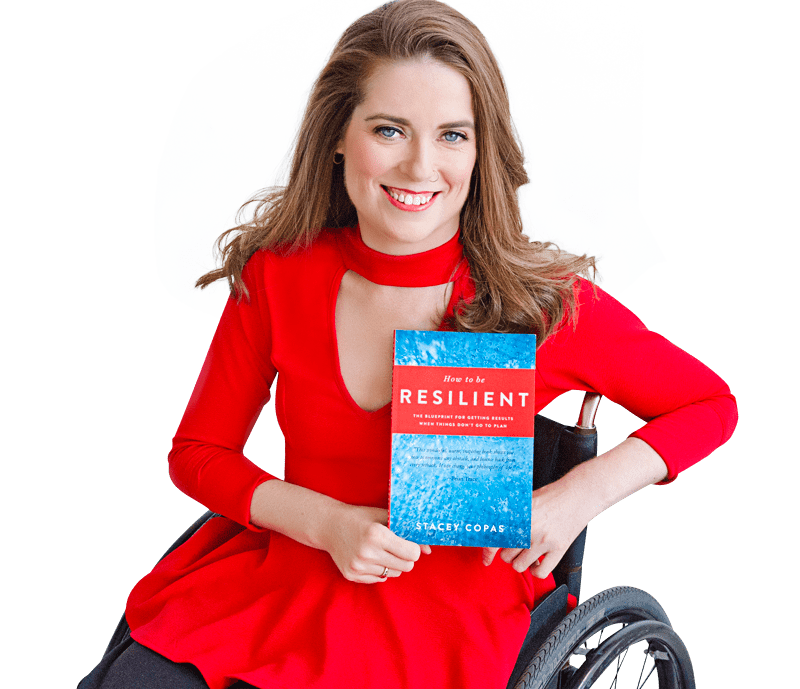

So, I did! I wrote a book, How To Be Resilient, delivered keynotes at conferences, and now I’m building online communities, delivering online programs, doing coaching and consulting, running workshops and, oh, I’ve just started a podcast as well! I feel that I’m really putting myself out there because resilience is needed now more than ever, both in the corporate setting, but also for kids and teens as well. I am able to share with them what I went through, and how I developed resilience as a result, and they can, too.

AM: This is fantastic! I wish you all the best for your business and making an impact, Stacey. On the topic of developing resilience, would there be one final message or take away in this that you would leave for our readers?

SC: One thing is, you can train yourself a little on what you choose to focus on. Like, I try not to focus each day on how hard things are, or the things that are harder because I had a spinal injury. If I do that, I find it weighs me down as a heavy energy. Instead, I write a journal at the end of every night. I write a sentence that begins: “Today, I had the opportunity to…”

AM: Today, I had the opportunity to interview Stacey Copas, and it was amazing. Thank you, Stacey.

For more information, go to Stacey Copas’ Academy of Resilience.

Angela McKane works with early-stage startups focused on developing solutions across the defense, transport and energy sectors. Prior to this McKane was VP Technology Insights at bp, where she grew and led a global team for over a decade, delivering actionable insights on emerging technology innovations and investment opportunities to teams across the Group. Earlier in her career, McKane worked at Transport for London (“TfL”) and, prior to that, she worked at her alma mater, the University of Glasgow. McKane is a regular speaker at industry leading conferences including Gastech, CERAweek and more. Connect with McKane onLinkedIn.

Oil and gas operations are commonly found in remote locations far from company headquarters. Now, it's possible to monitor pump operations, collate and analyze seismic data, and track employees around the world from almost anywhere. Whether employees are in the office or in the field, the internet and related applications enable a greater multidirectional flow of information – and control – than ever before.