“It was an opportunity women my age could have only in Alaska,” Joey Roth, a veteran drilling engineer for Shell, says of working on the Trans-Alaska Pipeline (TAPS) in 1976. “They didn’t care if you were a woman or black or green; they just needed people to do the job.”

It’s [now] been 50 years since the number of workers on TAPS peaked at 28,000, according to the Valdez Museum History Archives, and at times women comprised as much as 10 percent of the workforce (higher than the eight percent mandated by law at the time). Thanks to the 2020 Hulu miniseries, Mrs. America, there is renewed interest in the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), ratified by Alaska April 5, 1972, which, in part, enabled these women to be part of the history-making Trans-Alaska Pipeline.

Sculptor Malcolm Alexander (1924 – 2014) illustrated the diversity of the TAPS workforce with the bronze sculpture he completed in 1980 that stood at the entrance of the Valdez Marine Terminal until 2017 when it was moved to Kelsey Dock. Comprised of five figures, the statue features a female Teamsters member as well as an Alaska Native (minorities made up 14 to 19 percent of the TAPS workforce).

With the end of an era – bp pulled out of its Alaska operations in 2020 (bp Pipelines, Inc. owned slightly more than 48 percent of TAPS) and Hilcorp took over – it’s vitally important that these stories be preserved.

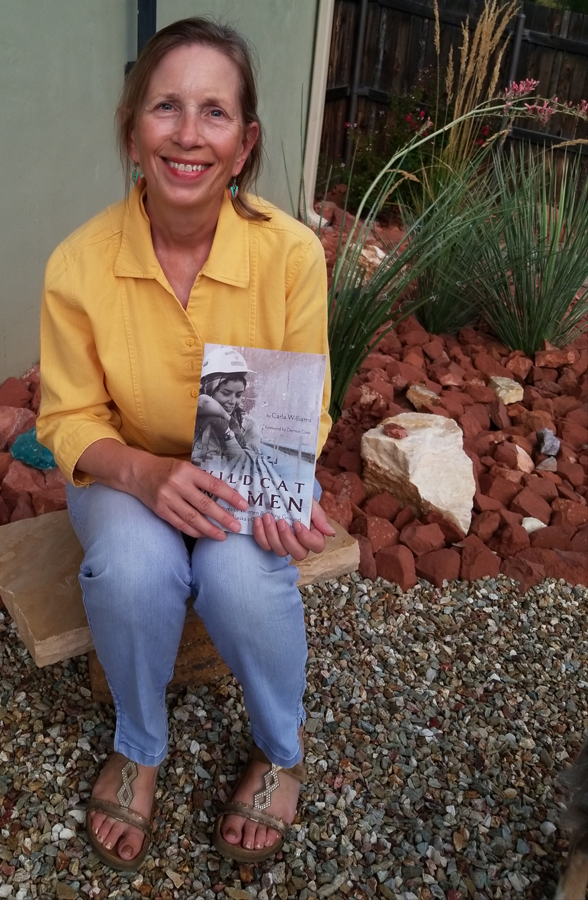

Author Carla Williams arrived in Anchorage in 1974 and writes, “A summer’s folly turned into 40 years.” Although construction of TAPS had been completed in 1977, the lure of high-paying jobs in the petroleum industry was still attracting large numbers of young people to Alaska.

“Most of us were idealistic,” she says. “We were opportunists and we didn’t care how we were perceived. Woodstock had happened and we were in this huge baby boomer generation that was [energized] even more by being in Alaska with this big project.”

Trained as a bookkeeper, Williams originally worked in the office for oilfield service joint ventures, working her way up to office manager/controller. She later became an engineering aide, eventually working herself into a lead engineering position on drill site projects “due to the scarcity of engineers in those days.”

“Every week, you could look at your paycheck and say, ‘Wow, I made this. I worked hard – seven days a week, 12 to14 hours a day – but it’s worth it.’ How many jobs could women say that about? [Opportunities] were few and far between where women could actually be proud of the money they made, money they earned and deserved.”

Even then, neither she, nor the women she would go on to profile in her book, Wildcat Women: Narratives of Women Breaking Ground in Alaska’s Oil and Gas Industry (University of Alaska Press), thought they were “special in any way, shape or form; [we] were just doing [our] jobs.”

It wouldn’t be until the late ‘90s when she “tagged along” with a friend to a conference in Las Vegas – “more of a gathering of pipeline workers” – and heard some of the older women talk about their days on the North Slope oilfields that she had “the first spark of recognition that there might be story there.” She began interviewing women in 1997 and would spend 18 years recording their stories. She found something remarkable in each.

Irene Bartee, who worked on the North Slope starting in the late ‘60s, tells of being flown to Kurparuk and not being allowed to disembark because there were no women there at the time. She eventually became a pilot herself and Williams marvels at Bartee’s ability to fly in Alaska’s famous “white outs,” not knowing where the runway was. “She was in the situation a few times in her life and it didn’t seem to faze her.” She also held her own against Jesse Carr, one of the top Teamster bosses at the time. “She had a lot of . . . ” Williams searches for the right word, “determination in getting her point across.”

Kate Cotton, who worked on the cat train and drove a Delta over the frozen tundra, talks about working in temperatures with 110 degrees below zero wind chill factor. “It’s hard for people to understand the barrenness, the isolation, and the loneliness,” some of the women had to endure, says Williams.

Rosemary Carroll, who had been working in Trading Bay as a roustabout, changed her plans, unbeknownst to her family, and took a later flight from Kenai to Anchorage to start her first day on the Slope. Tragically, the plane crashed and killed five of the seven people onboard, ensuring that day in 1987 was seared forever into her mind. Carroll went on to have a successful career as a control room board operator and says, “What a time it was and what a ride it’s been.”

Williams and her husband, whom she met in the mid-80s on a PRICE/CIRI construction project on the North Slope, retired in 2014 to Sedona, Arizona, where she is a hiking guide. Having been in the extraordinary situation [now 50 years ago] of being paid the same as her male counterparts – equal pay for equal work – she now hopes young women coming into the industry will have the same opportunities.

Reprinted with permission. This article originally appeared on forbes.com on April 28, 2020. It has been lightly edited and updated for this publication.

Read a previously published excerpt from Wildcat Women by Carla Williams in the Nov/Dec 2021 issue of Oilwoman Magazine.

Rebecca Ponton is the editor in chief at U.S. Energy Media and author of Breaking the Gas Ceiling: Women in the Offshore Oil and Gas Industry. She is the publisher of Books & Recovery digital magazine.

Oil and gas operations are commonly found in remote locations far from company headquarters. Now, it's possible to monitor pump operations, collate and analyze seismic data, and track employees around the world from almost anywhere. Whether employees are in the office or in the field, the internet and related applications enable a greater multidirectional flow of information – and control – than ever before.