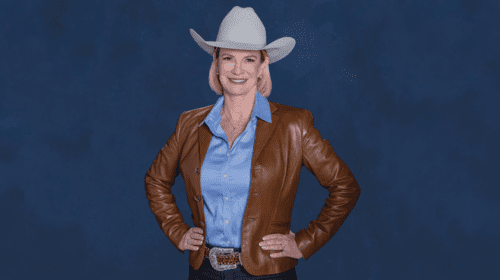

Imagine driving one hundred miles each way to and from your office – before loading up your crew and heading in a different direction to the day’s job site. As you cross the high desert and navigate the twisting roads through the ponderosa forests surrounding Flagstaff, Arizona, you have time to appreciate the sheer scale of the environment. Few paved secondary roads branch off your route, most are dirt tracks leading to off-grid ranches or farms. The sky is enormous; the views are endless. This is the drive that Deb Tewa, winner of the 2021 American Indian Science and Engineering Society (AISES) Indigenous Excellence Award, makes every day.

A member of the Hopi Tribe from Hotevilla, Arizona, Tewa has more than 35 years’ experience in the energy business. As the workforce and education manager for Native Renewables, a Flagstaff based non-profit, Tewa educates tribal members of all ages about the basics of electricity and solar electrical generation. She prepares students for technical careers in the solar industry. Native Renewables designs and installs off-grid, battery-based solar photovoltaic systems to power homes on the Navajo and Hopi reservations. The organization has also sourced and distributed small-scale solar appliance chargers for devices such as mobile phones, camp lights and rechargeable flashlights used in remote areas.

When Tewa applied to an electrical training program at the Gila River Career Center in 1983, she wasn’t sure that the course even accepted women. She had attended Northern Arizona University briefly following high school, but moved home after two years to work. She learned about the electrical certification program through an outreach program, was admitted, and found the work interesting. Tewa enjoyed learning the energy business from the ground up. Her skill was not just in wiring residential or commercial projects. Tewa’s supervisors quickly recognized her ability to communicate with competing groups, like plumbers or sheet rockers, vying for access to the same workspace on the job site. Tewa’s leadership facilitated timely project completion for everyone. As a result, she was promoted to electrical foreman early on, thanks, she says to “great mentors – all men – who invested in me.”

Tewa’s career took an unusual turn when she decided to move into the nascent solar industry in the 1990s. Working for a non-profit funded by the Hopi Foundation, Tewa earned photovoltaic installation credentials. She embraced the idea that solar panels could charge batteries, providing a more secure and affordable source of power for things like cell phone charging or basic night time lighting. Many Native Americans relied on gasoline-fired generators, batteries or sometimes even candles for light. Noting that tribal lands represent two percent of the United States’ land mass and contain five percent of renewable energy potential, Tewa worked to literally bring power to the people using an abundant Arizona natural resource: the sun. She led the installation of more than 300 solar projects that provided off-grid electric power to widely scattered Indigenous families.

Ten years into this work, Tewa realized that she needed to replicate herself if sustainable energy was going to grow. She returned to college and earned her Bachelor of Science degree from Northern Arizona University in 2002. She then helped create an extensive photovoltaic lab at Central Arizona College and worked at both Sandia National Laboratories and the Arizona Department of Commerce Energy Office before joining Native Renewables with the goal of creating a solar training program in Flagstaff.

“Our first cohort in 2019 included ten Navajo students, four women and six men, all with high school diplomas,” Tewa says. “Two are on-staff with Native Renewables part time now.” When COVID-19 shutdowns delayed the start of the second cohort, Tewa pivoted and redesigned the program. “We did one upskilling training for Cohort 1 via Zoom and it worked so well, we decided to get the five members of Cohort 2 going on a hybrid basis. We did theory via Zoom classes. Then the students came into the lab for hands-on work. Some of our first students came back to help teach the second class.”

The Native Renewables students have performed thirteen installations of 2.4KW solar powered battery systems to date in some very remote locations. “I measure distance in time, not miles, because the roads are so rough,” Tewa notes. “We’re driving big trucks and towing dual-wheeled trailers loaded with equipment over dirt tracks, driving around big rocks, just to set up the work site.” The weather of northern Arizona presents its own challenges, hot in the summer yet snowy in the winter.

Once the project is installed, Tewa and her team train the household on the use and maintenance of their new system. “Our customers appreciate learning how the battery should be operated on cloudy days, for example, or that they should only use LED light bulbs to minimize draw,” Tewa says. “We’re always available to speak with people in the language – Navajo, Hopi, English – most comfortable for them. We want to meet their needs.”

Tewa is concerned with educating young people, especially women, about their options. Although only about 25 percent of solar technicians nationwide are women, “We don’t just push the solar installation work. Our community needs engineers, inventory people, operations staff. My goal is to help people find a good direction for their career.”

Tewa says she was “humbled and honored” to be selected for the 2021 Indigenous Achievement Award. Deflecting from her lifetime of service, she says she prefers to look toward a future of increased capacity to help people in her community. “More financial security for the program, more trucks, more people capacity – that’s what I think about.”

Headline photo – Deb Tewa in Second Mesa, in Navajo County, Arizona, on the Hopi Reservation. Photo courtesy of the American Indian Science and Engineering Society.

Elizabeth Wilder is a freelance writer based in Houston, Texas.

Oil and gas operations are commonly found in remote locations far from company headquarters. Now, it's possible to monitor pump operations, collate and analyze seismic data, and track employees around the world from almost anywhere. Whether employees are in the office or in the field, the internet and related applications enable a greater multidirectional flow of information – and control – than ever before.