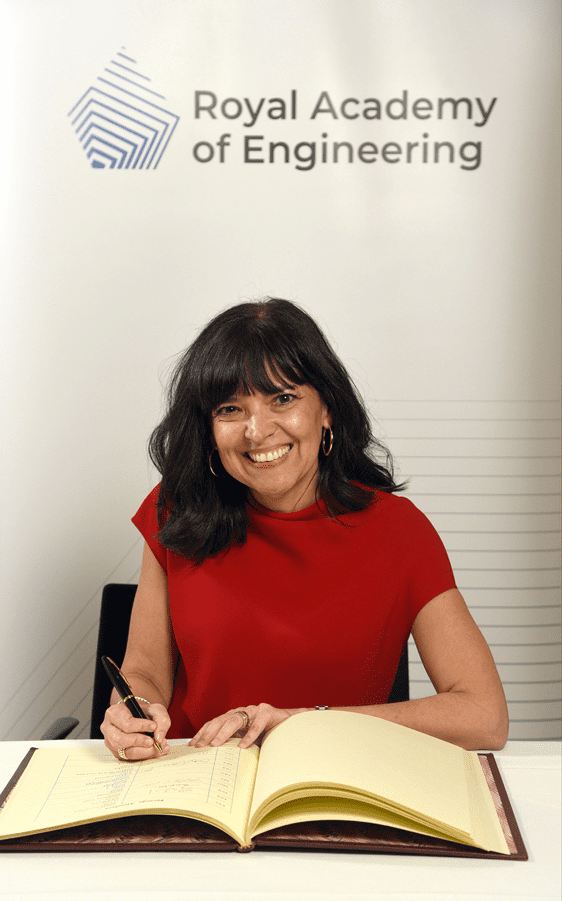

“It was extremely humbling,” says Aleida Rios of being named an international fellow of the U.K. Royal Academy of Engineers in 2021. “I’ve always been an engineer at heart. It’s something I love, but I certainly never expected this honor.” She was even more surprised to be the first Latina among “this amazing group of the best engineers in the world. My job now is to pay it forward and make sure it doesn’t remain that way.”

Rios, a 30-year veteran of bp, who started her career at its predecessor, Amoco, is known in the industry for her passion for advocating for young girls and women in science, technology, engineering and math and says resolutely, “I’m not stopping until we see parity across all those STEM fields.”

Having grown up in a small, rural town in Mexico, where there was no running water or electricity, and school only went through the fifth grade, Rios is acutely aware of the importance of being a vocal and visible advocate for young girls and minorities who otherwise might not have one. Both of her parents received only a fifth-grade education, but Rios refers to her mother fondly as a “status quo buster,” who encouraged her two daughters, as well as her two sons, to get an education, particularly as she did not want the girls to be dependent on anyone.

Rios’ family recognized the privilege of having an education and they immigrated to the U.S. for the same reasons many immigrants do. “The American Dream is the possibility of a great education and the prosperities that come with it,” Rios says.

Despite growing up “poor,” Rios says it was a happy childhood and she has fond memories of returning to her grandparents’ rancho in Mexico in the summers. “It was great fun. At the end of the day, everybody would come in from the fields and it was exciting because we got to hook up the batteries in the truck to have an hour of TV at night before the lights went out.” Because of her childhood experiences, and living between the “two worlds” of Mexico and the U.S., Rios says the importance of access to reliable electricity is “ingrained” in her and concedes it may have influenced her decision to eventually pursue a career in the energy industry. But, first, she had to learn English . . .

Rios was eight when her family immigrated to the U.S. and found themselves in a socially and economically depressed part of Houston; however, the city wasn’t as diverse in the late ‘70s as it is now. At school, there was no one else she could speak Spanish with and no one to translate for her.

“Math was one subject I didn’t need anybody to translate for me. One plus one are symbols that are universal.” Rios says she excelled in the subject and, eventually, because of her high grades, was bussed to a different school zone, where she attended middle school at the Math and Science Academy. In what was, perhaps, a harbinger of things to come, she later enrolled in a magnet program at the Milby High School for Oil and Gas Academy.

“I wanted to go to the school that had the best education. My parents had no idea what an engineer was. I just knew that I was making good grades and wanted to excel.” She also needed to work and took extra classes in order to be allowed to participate in a work release program. “I started working at 16 as a cashier at Kmart and they promoted me very quickly.” Because of her aptitude for math, she soon became head cashier.

Then, as a senior at Milby High School, one of her teachers, who was a chemical engineer, told Rios she thought she had the potential to be an engineer. She took “zero period,” which enabled her to go to school early and get out early, so she could work. It was then that she got a job in a lab at the Shell refinery. Working there, in addition to the teacher’s comment, planted the seed in Rios’ mind that she could be an engineer.

“The reality is, I liked chemistry and I liked math, so I applied for a chemical engineering degree at Texas A&M and received a scholarship. I was the first person in my extended family to go to university. As I said, my mother has always been a little bit of a status quo buster and I think that’s also why I picked engineering because I thought, ‘What is the hardest, most challenging degree I can get?’ My parents had given up so much for me, I definitely was going to make it worth their while. So, I’m a bit of a trailblazer in my family!”

Rios tells that story, in part, to underscore the need for visible and vocal role models. “We all have biases. We have to break those biases, like my mother broke them, like the biases my teacher broke – I call women like them “status quo busters.” It’s important because we know that diversity creates value and we need to make sure that we break those biases and focus on the equity and inclusion part of STEM.”

After the refining job at Shell, Rios enrolled in another program and spent four summers during college interning with Amoco (now bp). “So, you can imagine the progress I’ve seen in 30 years!” she says with a smile that lights up her whole face.

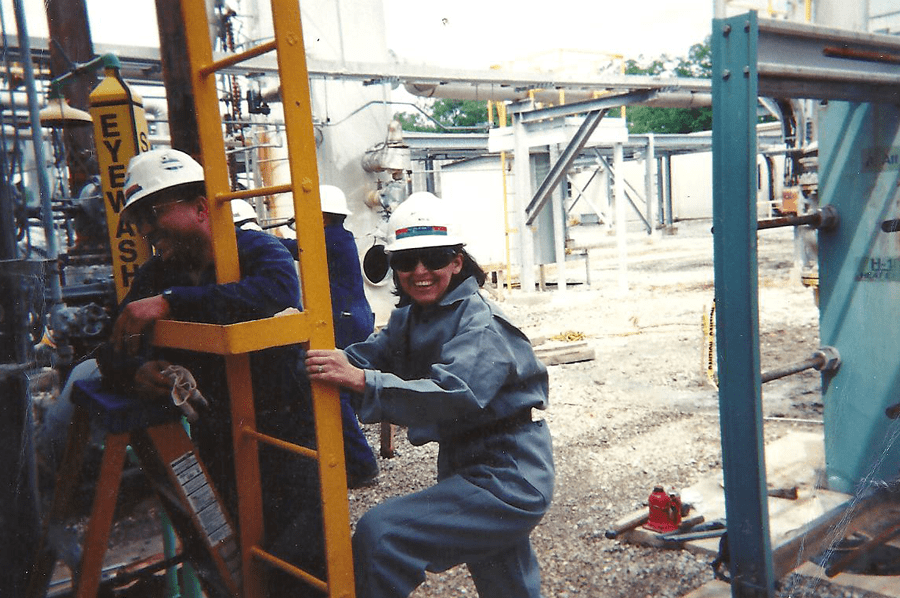

At the start of her career, Rios, who loves a challenge – and the more difficult the challenge, the more it appeals to her – went to West Texas and worked as a roustabout. While she says it was a daunting experience at first, “I always say, if it scares you, go for it, because that means there’s a lot of growth in it.”

She believes she inherited that fearlessness from her mother, “who had to have been scared to death to come to a different country. I think she instilled that in us – ‘don’t be afraid; you can do this,’ and then, slowly, it gives you courage.”

That belief in herself has carried Rios far. After three decades at bp, she has risen to senior vice president of engineering, and part of her role is to develop over 2,500 engineers in bp’s workforce. Despite the focus on STEM, women only make up 13 percent of the engineering workforce, according to the Society of Women Engineers (SWE); however, women comprise 20 percent women bp’s engineering workforce – “not quite parity,” Rios points out, but certainly well above average. Her team is 40 percent female, and they are the most senior chief engineers in the company. However, it is not only about attracting talent, but retaining it. “It really starts from that very early education in those primary math classes through to college through to wanting to stay in engineering. We have to constantly work to ensure there are no leaks in the pipeline.”

Thirty-nine percent of bp’s top leadership is also female, which is much higher than what is seen across the industry, and a figure Rios expects the company to exceed in the near future. “Our ambition is for bp to be a company where gender balance is evident. To this end, our aim by 2025 is to have at least equal numbers of women as men in our 120 most senior leadership roles and 40 percent women in the next level of leadership. By 2030 at the very latest, our goal is to have women filling at least half of our all-senior leader roles and 40 percent at every other level of the company. It’s not just about the ambitious goals; it’s also making sure that we have a framework to drive that accountability. We focused on progressing gender representation and I have seen it happen in my career.”

Recruiting and retention are built on a critical framework that Rios says are centered around three pillars: transparency, accountability and talent.

Transparency is driven through internal and external progress reports. “Building and developing that potential in women – and all underrepresented groups – across the entire pipeline is hugely important,” but people have to see evidence of a company’s metrics to believe it, Rios says. “When people see your diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) report, they want to be part of your organization because everybody wants to work in a team; they want to feel like they belong. I think that what attracts talent retains talent.”

bp’s culture is, in part, what has kept Rios committed to the company, where she says she’s had “multiple careers” over the last 30 years. Being with a large, global corporation that is fully integrated across the energy spectrum has enabled Rios to stay motivated and apply her engineering knowledge and expertise in a variety of ways in different areas of the company. Now that bp is “reimagining energy,” she is embracing the challenge of new sectors where she has never worked before.

“It’s like I’m in a different company,” Rios says. “There’s so much opportunity within bp that you feel like you can move around without being stagnant. I’ve also stayed because of the culture that made it possible for me to be successful and allowed me to continue to be that status quo buster!”

Rios describes herself as being “super excited” by the energy transition – “It’s imperative that we do this, so that’s something that is always driving me” – and the publicly stated company goal of reaching net zero by 2050, or sooner. While Rios says people focus on that particular part of bp’s strategy and ambition, she stresses it is the company’s goal is to help the world get to net zero. “The energy transition is really a problem of both pace and capability. I definitely believe we have the ability to solve the technology problems, but it’s going to need to be done sooner.”

Rios, who sits on the Energy Institute Science and Technical Advisory Committee (STAC), says, “It’s a common set of engineering standards that will enable us to transform knowledge across the industry and across the international boundaries and languages, and enable a faster learning curve. We’ve always depended on those standards, but I think they’re hugely important in the energy transition, even more so because of the pace that we need to get to net zero.”

STAC works across industry to collaborate to provide one set of standards. Industry groups, such as API and IOGP, represent the full spectrum of companies working and learning together, driving collaboration and innovation.

“It’s also really exciting because engineers are at the forefront of creating those solutions to deliver the challenge of the energy transition. It is a physical problem; it’s something that we have the capability of solving. We’ve always raced to learn to find solutions to very complex physical problems. There’s no greater challenge today than the energy transition in order for everybody to have clean, reliable, accessible energy.”

In thinking about the legacy she wants to leave, Rios would like to be remembered, not just as an engineer who had an amazing career, but also one that left a legacy behind for others to continue. “The world needs us to all be part of this transition and part of the solution.”

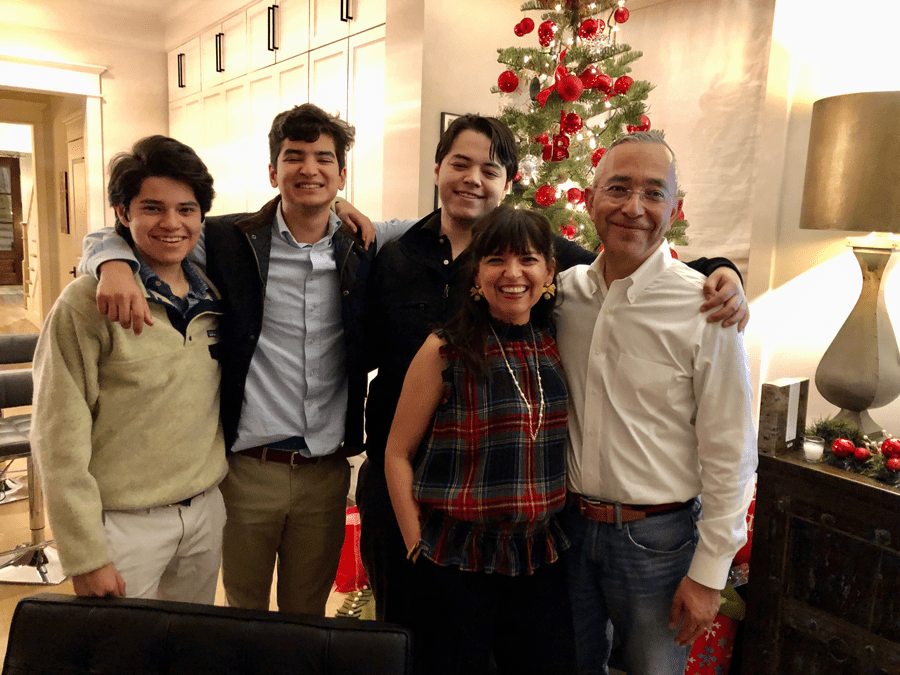

“My three boys have always known Mom is trying to make the world a better place. They used to say, “Mom is turning on the lights,” but they know I’m helping bring energy to the world.”

Headline photo: Aleida Rios on bp’s Argos platform in the Gulf of Mexico (July 2021). Photo courtesy of bp.

Rebecca Ponton is the editor in chief at U.S. Energy Media and author of Breaking the Gas Ceiling: Women in the Offshore Oil and Gas Industry. She is the publisher of Books & Recovery digital magazine.

Oil and gas operations are commonly found in remote locations far from company headquarters. Now, it's possible to monitor pump operations, collate and analyze seismic data, and track employees around the world from almost anywhere. Whether employees are in the office or in the field, the internet and related applications enable a greater multidirectional flow of information – and control – than ever before.